Year Published : 1819

Year Published : 1819

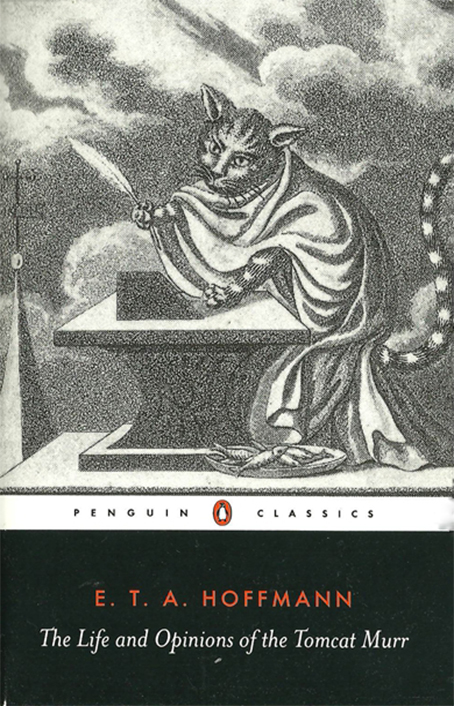

Author : E. T. A. Hoffmann

Publisher : Penguin Classics

Genre : 19th Century, German Literature, Surreal

Pages : 320

Blurb : Tomcat Murr is a loveable, self-taught animal who has written his own autobiography. But a printer’s error causes his story to be accidentally mixed and spliced with a book about the composer Johannes Kreisler. As the two versions break off and alternate at dramatic moments, two wildly different characters emerge from the confusion – Murr, the confident scholar, lover, carouser and brawler, and the moody, hypochondriac genius Kreisler. In his exuberant and bizarre novel, Hoffmann brilliantly evokes the fantastic, the ridiculous and the sublime within the humdrum bustle of daily life, making The Life and Opinions of the Tomcat Murr one of the funniest and strangest novels of the nineteenth century.

312 Book Review : In this wonderfully playful and yet highly complex novel, Hoffmann displays his talents for story telling with the endearing confidence of the eponymous Tomcat Murr.

The premise is this. An autodidactic cat has written an autobiography of his life on the back of leaves of paper ripped from a previously written book on the famous composer and kapellmeister Johannes Kreisler. As the editor of the novel explains, the printers neglect to notice the irregularity and print Murr’s autobiography so that it is fused with that of Kreisler. The end result is a jumble, two stories in one, so that as Tomcat Murr’s adventures build to an exciting conclusion the story breaks off into that of Kreisler and vice versa.

It’s a novel that shouldn’t work, indeed initially it doesn’t seem to, but the convoluted and byzantine nature of the book does, somehow, begin to knit together as the author slyly slips clues into the narrative that spark realisations and connections into the readers mind without ever giving too much away. Soon the reader becomes engrossed in the fantastic sphere of gauche intellectual cat Murr and the odd world of Kreisler, part magical toy-like princely court, part high minded theological and philosophical wrestling, part threatening and inspiring Nature.

The two interweaving halves of the novel straddle the intellectual schism of the day, the two opposing philosophical doctrines of the 19th century – the Enlightenment and Romanticism. Murr represents the Enlightenment scholar, unworldy, naive but over confident and clear minded, who stays within his small but learned home reading and studying the intellectual tomes of his owner Master Abraham and who teaches himself to write and compose poetry, at least until he discovers and becomes distracted by street life. Kreisler is the diametrically opposed figure, the Romantic genius, a creative titan, yet insecure, moody, directionless, an outsider, always questing for answers about life that only lead to more questions and plagued by demons of self doubt that are so severe he has virtually written himself of as a madman, someone who’s talents can never segue into normal society.

At first Tomcat Murr’s story is the most engaging, as the endearingly arrogant Murr, convinced of his own intellectual superiority, critiques both human and cat life. Strangely, the human based story seems bizarre and far fetched in comparison, set in a fairy tale like minor German principality full of eccentric aristocrats, wise old men who meddle in magic, strange gypsies and, of course, the oddly behaved Kreisler.

Yet over the course of the novel a subtle switch in the perception of the stories occurs. As Tomcat Murr discovers life outside his scholarly quarters and picks up the base habits of street life, forming bigotries, losing trust in his friends, aligning himself with cliques, brawling, drinking and philandering, his former charming assurance becomes debauched and repugnant. The opposite can be said of Kreisler’s story. Initially introduced as a rude, slightly frightening and moonstruck loon, the more we learn about him, the more we are drawn to his complex personality and the intrigues he finds himself enveloped in. Kreisler’s story is slow burning, at times, like the man, frustratingly complicated, but ultimately more satisfying.

The contrasts between the main characters are evident. Yet there are connections, both are linked to Master Abraham, both are estranged from their true love, both find themselves in a deadly duel, both are, ultimately, outcasts of society, belonging neither in higher society or among the common folk and both find solace and purpose in intellectual creativity. Inscrutably sybilline as life is, domineering, coercing, checking the choices of near powerless individuals, perhaps then individuality can only be understood by the universal themes that affect all of us – identity, love, struggle, the search for belonging and happiness. Even characters as apparently opposite as Tomcat Murr and Johannes Kreisler.