Author : Saul Bellow

Nationality : Canadian / American

Publisher : Penguin Modern Classics

Genre : 20th Century, American Literature, Jewish Literature, Postwar

Pages : 340

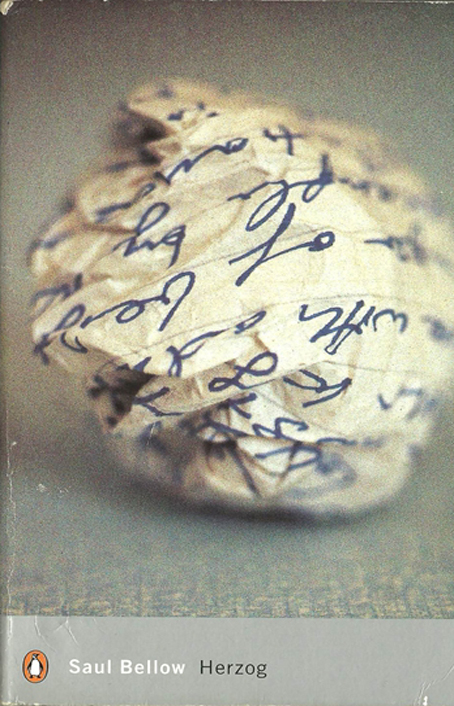

Blurb : Is Moses Herzog losing his mind? His formidable wife Madeleine has left him for his best friend and he is left alone with his whirling thoughts, yet he still sees himself as a survivor, raging against private disasters and those of the modern age. His head buzzing with ideas, he writes frantic, unsent letters to friends and enemies, colleagues and famous people, the living and the dead, revealing the spectacular workings of his labyrinthine mind and the innermost secrets of his troubled heart.

312 BOOK REVIEW : Not much happens in Saul Bellow’s ‘Herzog’ until the end of the book when Herzog’s thin grasp on sanity seems to slip resulting in a tense ‘will he, won’t he’ scenario that is soon superseded by a unexpected accidental event that leads to partial mental resolution for the protagonist.

Herzog is an intellectual, once a promising one, who has fallen by the way side. Lauded for his academic writing and study of romanticism and religion, he develops an almost messianic delusion that he can find meaning in modern life through his own intellectual gifts and thereby save the world. This suggests Herzog was always liable to tumble into madness, this conviction that some meaning could be found through focused intellectual vigour is really only a kind of socially acceptable insanity in the eyes of the intelligentsia who are his peers, lovers and friends.

However, his world disintegrates, his focus is lost, his misunderstandings are exposed when his second marriage breaks down acrimoniously. One suspects the reason Herzog’s cold blooded, constantly evolving wife, Madeleine, destroys the marriage by having an affair with his best friend, Valentine Gersbach, is sheer contempt for a husband she has grown to hate while living in an isolated country retreat.

There after Herzog suffers what can only be described as a mental collapse. Already middle aged, his body beginning to fray, now his mind also starts to come apart. Lost, hurt, betrayed, he examines his life and its place in modern society in excruciating detail. He does this for the most part by jotting down letters, never sent, often only fragmentary, to past lovers, family members, academics, friends, famous thinkers and politicians, living and dead. This thoughts are a mess, indeed they make difficult reading and are difficult to fully understand. They also disrupt the natural narrative of the story considerably and hamper Bellow’s otherwise stylish prose. However they do successfully convey that Herzog’s travails of the heart, his upbringing, his relationships with wives and lovers have left him at the point of being crushed by his realisation his entire life has led him into a metaphysical cul-de-sac.

If the book has any answers they are not especially original. Everything comes down to love and death. Death, fear of dying drives intellectualism. Every discovery, every act of enlightenment is simply an inadequate substitute to temporarily appease the uncertainty of what lies beyond the mortal world. Deaths shadow looms over everything and cannot be escaped, it does not merely influence human decisions and events, it dictates them. God is dead, Death is god.

What then for the living? Well it seems, judging by the behaviour of Herzog’s peers there are four options. Firstly, a sort of unthinking obsolete ignorance that clings to the old ways, religion mainly, and completely ignores modernity. This of course is a form of faith based unreality, perhaps even moral cowardice by refusing to accept an age where mounds of Herzog’s Jewish kin have been buried by bulldozers. Next there is the mean, hateful hyper reality represented by Herzog’s lawyer Himmelstein. There is no morality because there is no god. The world isn’t worth a damn and neither are the people who populate it. You take what you can. You make your own selfish happiness where you find it and where there is none you distract yourself by clawing your way towards base desires. Life is something like Hobbes meets Darwin – nasty, brutish and, thanks to the species dominance of the earth, long and lengthening.

Thirdly there is Herzog’s primary mode of consciousness, to find some kind of meaning in life, some plan, a blue print, something that can be understood with the mind. However, that puzzle is intellectually unsolvable and based on an idea of a super human individualism that is in itself a fallacy. It’s worth noting Herzog’s acclaimed academic work is entitled ‘Romanticism and Religion’, which suggests he is torn between two incompatible ‘truths’, one offering only paradise in death, the other offering only a void in life, with Herzog somewhere between, tortured by the inexplicable Something he has, a little love, a little success, a few friends, enough money. Herzog realises he will never completely fail and it is this that elicits his screams for freedom.

Finally, we have love. Perhaps the most satisfying moments of the novel are Herzog’s relationships with his family. While lovers, indeed wives, come and go, family will always be in a man’s heart. Herzog’s relationship with his daughter is touching, it is obvious that simply seeing the child he has lost daily contact with calms his excited, half mad mind. Being told his young daughter will forget him and accept his traitor friend Gersbach as her new father is perhaps the driving force behind his slackening grasp on sanity but when it transpires familial love is stronger than simply being exposed to a person in place and time Herzog finds succour.

Towards the end of the book, Herzog’s brother Willy appears. Herzog is to all extents and purposes a nuisance, a brother who doesn’t keep in touch, someone who only phones when he needs money or is in trouble but Willy goes out of his way to help Herzog. Willy loves his brother. Herzog loves Willy, loves all his siblings, his son, his daughter, his dead mother and father. With family, unlike with Madeleine, personal disappointments do not breed hatred, they fortify and strengthen.

In ‘Herzog’ it is familial love that provides mental security from battering life and its passing tempests of betrayal and failure and from the looming shadow of death with all its sinister mysteries.